I received two kinds of offers for Grace Fury.

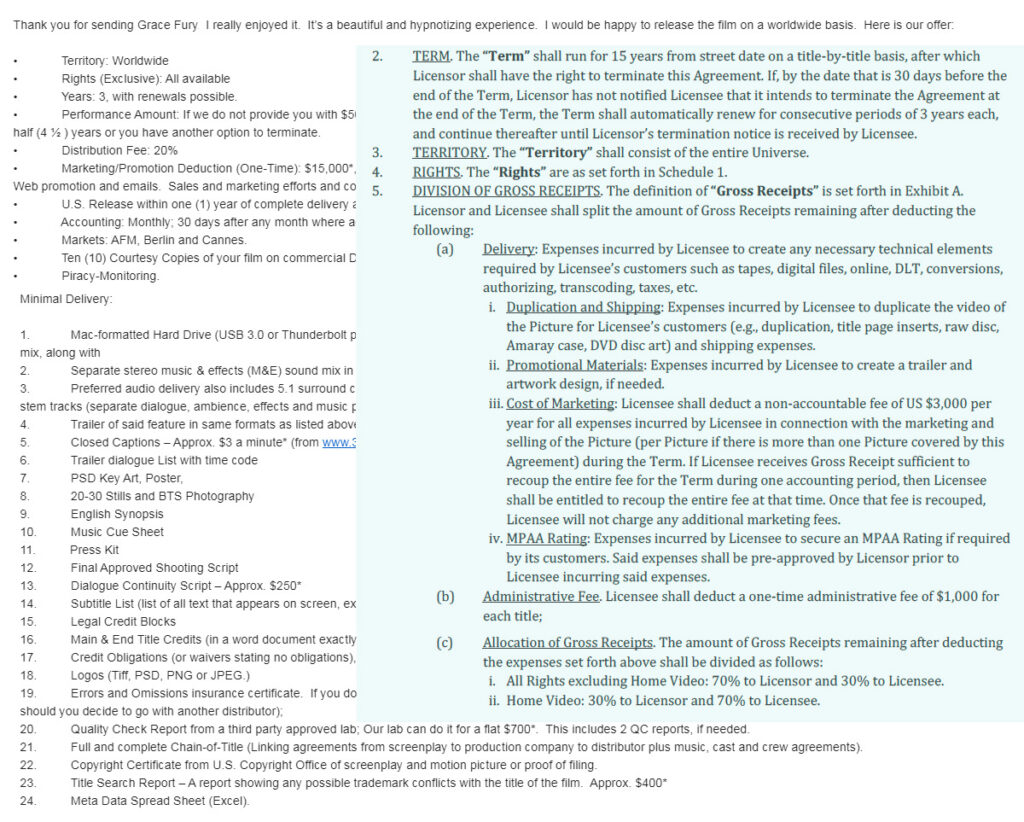

Company #1 takes the film for at least three years and a $15,000 fee – or that fee plus a percentage of any offer. If unable to land a deal in that time, I get my product back, less the years lost and those fees for prep and “marketing”.

Enough complaints from filmmakers and promoters warn me. The “marketing” efforts of these companies are minimal. Arguably their fees would be much larger, if they really were campaigning diligently and specifically for you. They’re not PR firms. The bulk of that task and risk is still yours. Otherwise, those fees mostly help them to attend and enjoy a few, giant market festivals on behalf of your film – and all of the others they have acquired.

Company #2 won’t collect a fee, if the film remains unplaced (or so I was told over the phone – not in contract). However, the company takes the film for 15 years, while reserving the right to collect $3,000/year “marketing costs” for that full term, plus a sizeable percentage (70%), if a home video deal is secured anytime in that period.

At this point, my agent let me know that most contracts would be akin to these. They write the rules with no mid-term escape clauses for the filmmaker.

Considering the fees or years separated from your major asset,

you’re basically paying for a loss of rights / control

and

(if they don’t succeed) for a lack of public exposure / return.

If nothing else, they could take it to Amazon, but so could you, less their fees and deductions.

To my reasoning, these companies are just another kind of agent who acquires product – for low-to-no investment profit, if things work out for you…and for their own loan appeal and security, if things don’t work out for you.

In fact, many of them fully admit they also produce their own films.

Your work and your long-term contract with them serve their own production needs.

You effectively grow their borrowing power, business profiles and marketing materials, even if your film goes nowhere under their control.

Unless you’re convinced of their ethic, abilities, and relationships with buyers, or you just want to say you’ve successfully passed your film on to a third party, you’re left with option three: DIY.

I dropped the search, and set my sights on self-distribution with new trailers and updated EPKs (electronic press kits) and newfound PR advisors who told me to wait. We were in the first year of COVID-19 after all and approaching the holidays. Surely, the spring of 2021 would give us more time, a better time, to launch, or so I thought, unaware that Amazon was on a mission of its own.

By the time we approached the DIY marketplace, this popular warehouse monopoly was already well into genre rejection and purge.

According to one fellow filmmaker, the company was dropping titles without warning. All new submissions to documentary, music video, concert, unique, “unsupported”, art house categories, etc. — unwelcome.

Not nice, but for the industry-independent artist, with or without Amazon,

the problem still typically and overwhelmingly remains: public relations / marketing.

Casual Amazon browsers don’t necessarily make a substantial or consistent audience for your film, if it’s not otherwise receiving attention or you’re not constantly targeting and tapping potential interest.

What you retain in rights and control over your work,

by not dealing with a middleman,

still faces all the challenges of promotion and all the obstacles to it.

The good, the bad, and the ugly in that department come next.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks